The other patient remarked, ‘You’re getting better.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘You talk. For three years we thought you were a mute.’

The entrance of the private hospital was sympathetically designed. Its front wall made of glass, forming a wide triangular gable at the top like a mid-century modern chapel. Tall sliding glass doors set in a white frame. External walls rendered in white and cream cement. A pale extension of the pitched roof sheltered the patient drop-off area, which doubled as an ambulance bay. Skylights along the roof line. Inside, lounge chairs placed around circular coffee tables. The foyer was warmed by morning sunlight, dappled with the shadow of leaves.

It was only on closer inspection that you could tell.

The doors didn’t slide open automatically, via sensor, but were activated remotely by calm receptionists. Their office was a built-in kiosk, desk positioned beneath a large rectangular opening. In an instant, the room could be sealed by a rolldown metal security shutter. After office hours, visitors pressed a small red button to the right of the front doors, monitored by a camera so discrete I never figured out where it was.

I only saw one patient make a run for it. He hovered near the entrance and bolted as a visitor entered. Within seconds, a group of male psychiatric nurses in crisp navy uniforms appeared, already sprinting. Glass doors slid open again. The men didn’t break stride.

At the beginning of each admission, a nurse asked a long list of questions and noted my answers on a multi-page form. Sobbing, I nodded or shook my head. An inch-wide plastic strip was fastened around my left wrist: red, for allergy. It looked like the kind used at music festivals. Except it was printed with my name and a bar code linked to medical records. My bags were inspected and an iPhone power lead taken to be checked by an electrician, labelled and kept at the nurse's station. The nurse ran gloved hands over the lining of my empty bag, frisking for contraband.

A small sign on the wall advised patients not to hang wet towels on the rails of privacy curtains enclosing each wheeled bed, because they were lightly secured and would fall. All hanging points had been removed. The door to my first room had a small window. Each hour, a nurse peered through it, opened the door and asked my name.

Our beige rooms lined a long, circular corridor several metres wide, grey carpet dotted with orange lounge chairs and round coffee tables of pale, laminated wood. Patients who were not allowed to leave hospital grounds walked the loop in slow laps.

Twenty-four-hour care by specialist nursing staff was divided into two units, each with a small, locked room of medication. Morning and evening, patients queued for tiny paper cups of pills and a plastic cup of water. If prescribed by their psychiatrist, a limited amount of diazepam was dispensed throughout the day pro re nata – as needed. Opposite the nurse's station in unit two was a small room with soundproof glass walls, soft black pleather couches and a television mounted behind a thick sheet of Perspex. Underneath, a bookshelf of thumbed paperbacks.

Meals were eaten in a large cafeteria, with menu options hand-written neatly on a small whiteboard at the entrance. Orange stackable chairs surrounded large white plastic tables, to encourage socialisation.

Patients queued, handed a ceramic plate to benevolent kitchen staff behind a hot food display counter. We gathered metal cutlery from stainless steel containers. After, each patient took their dinnerware to a trolley, scraped leftovers into a bin next to it, and slid crockery and cutlery into large tubs of soapy water. On exit, a nurse checked nothing was removed.

At the centre of the building was a garden, walled by patient rooms with windows open for fresh air but curtains mostly closed. Trees dotted a lawn of clipped buffalo grass on which I sometimes lay to bask, fully clothed, in the sun. It was bordered by tussocks of burnished orange kangaroo paws and wild iris with white, yolk yellow and pale lilac petals. Carved graffiti scarred the grey wood of a picnic table, the ground underneath it rubbed bare.

The peaceful setting was punctured by sounds of despair: guttural wailing, soft sobs, an abrupt yell. Drifts of conversation between patients and psychiatric staff.

'But I'm telling you, I can fly!'

'That's not the topic we are discussing.'

The swarm of male psychiatric nurses reappeared occasionally, sprinting toward an emergency.

On weekdays we were encouraged to attend group therapy classes. There, psychologists taught strategies to cope with our symptoms, process trauma and re-learn the basic skills of living.

At first, I silently categorised other patients by their diagnosis: bipolar, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, addiction and so on. Over time, as I learned more about them, I categorised by cause: trauma, abuse, assault, tragedy, grief, victim of crime, war, possibly genetic and unknown. Occasionally, a criminal defendant was brought in to be psychologically assessed or detox from drugs.

When I couldn't sleep, I paced the corridor 'til dawn and watched patients pushed in wheelchairs from electroconvulsive therapy to a recovery room for observation. Bodies limp, skin flushed, with expressions of dazed terror.

Sometimes they called out, 'Who am I? I don't know my name.'

'Where am I, what's happening to me?'

Their brief distress was soon forgotten, along with other more meaningful memories that may or may not return. A few weeks later I'd see them walk the corridor, heading home. The gait of their hopeless shuffle transformed to confident stride, as if by miracle. Until next time.

Outside hospital walls, friends married and had children. My brother visited with his toddler son. Some former patients died by suicide.

I remained, stuck in a cycle of trying new medications then weening off them due to inefficacy or overwhelming side effects. Over the years, before and during hospital, these included fluoxetine, escitalopram, sodium valproate, lithium carbonate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, quetiapine, bitter asenapine wafers dissolved under my tongue. Others I've forgotten. Diazepam, which was milder, the dose increasing as I developed tolerance.

Twenty transcranial magnetic stimulation treatments on consecutive days. Then another ten. While seated in a comfortable recliner, a black object shaped like a filled-in number eight, a few inches thick, was angled above my right temple like a hovering fascinator. The object used a magnetic field to pulse electrical currents, which felt like invisible fingers penetrating skull to gently massage my brain.

Some people read or slept. I wept uncontrollably or talked incessantly to the supervising nurse. The dam of my reserve burst, then re-sealed the moment a session was over.

My depression decreased in severity. The treatment ended when I told my psychiatrist I had static in my brain and couldn't concentrate enough to read. He cancelled plans for recurrent sessions. Above my right temple, the hair grew back white.

The succession of medications ended with chlorpromazine, prescribed in a small dose as a less physically addictive alternative to diazepam.

Within a couple of days my nose twitched, rabbit-like. Eyelids winced shut. I was less coordinated. I thought it was diazepam withdrawal.

My psychiatrist walked toward me in the corridor then froze in motion like a child playing statues. He composed himself.

'Please, come with me.'

We walked to his office, my limbs jerky, moving as if manipulated by an inexperienced puppeteer.

Inside, he instructed, 'Walk heel to toe, in a straight line.'

I tried to manoeuvre one foot in front of the other but lost balance, as if the invisible line on the carpet was a tightrope. Steadying myself, I tried again and grasped at a chair as I stumbled.

'Please sit. Close your eyes and touch your nose with your finger.'

I closed my eyes, moved my hand and waited to feel the sensation of fingertip on face. It didn't come. Puzzled, I opened my eyes. In my peripheral vision I saw my hand paused at the side of my head.

His face ashened. Jaw clenched. Shoulders slumped.

'I will get back to you.'

The medication was removed from my chart. But side effects continued to increase in severity.

A psychiatric nurse asked, 'Hazel, where have you come from, where were you a minute ago?'

I stared blankly.

'I d-on't. Knnnow.'

My head jerked repeatedly. Limbs twitched in brief convulsions.

'Myy. B-rain feels. Like an. En-gine that. Is. Mm, mm, misfiring.'

His voice was calm and measured but his expression grim.

'Yeah. Basically, that's it.'

'Hhands.'

We looked down. My wrists were involuntarily right-angled inwards, rigid. Fingers frozen into zombie-like claws.

The next time I saw my psychiatrist he took a long, deep breath. Exhaled slowly.

'On further research, I found that chlorpromazine should not be prescribed to classical musicians. They also experience severe dystonia. We think it is related to dexterity and exceptionally fine motor skills. Artists were not mentioned. However, you must be the same. You will recover. But we don't know how long it will take.'

He paused. Then enunciated with precision.

'I am so sorry.'

My face contorted, gurning like a raver at the end of a three-day binge. Seated, yet limbs in spasmodic flail.

'It's. Oh kay. Yyou. Caan't know. Ev. Ev. Every-thing.'

His eyes welled with tears.

Months later, I'd lost twenty kilograms – mostly muscle – from being bedridden and unable to keep my head still to be fed or guide cutlery to my mouth. I could not write legibly or walk without staggering. My speech was laboured but more fluid.

I told my psychiatrist, 'No more medication. I'd rather be mentally ill.'

He nodded. Sombre, shoulders still slumped.

Throughout my hospital years, our mum visited weekly with oriental lilies to perfume my room. She rinsed the soft clear plastic rectangle with horizontal blue stripes given to her by a nurse, which folded like origami into a three-dimensional vase, and refilled it with fresh-cut flowers. I measured the passing of time by their lifespan. Petals became translucent and withered. Often, it seemed to happen overnight.

A psychiatric nurse sat on a chair beside my bed and sighed, 'Hazel, you cannot remain tightly closed, like a bud refusing to flower. You must open up.'

Experiencing severe mental illness is like going to hell inside oneself. I don't remember why I started talking more. Perhaps I realised it was the only way out.

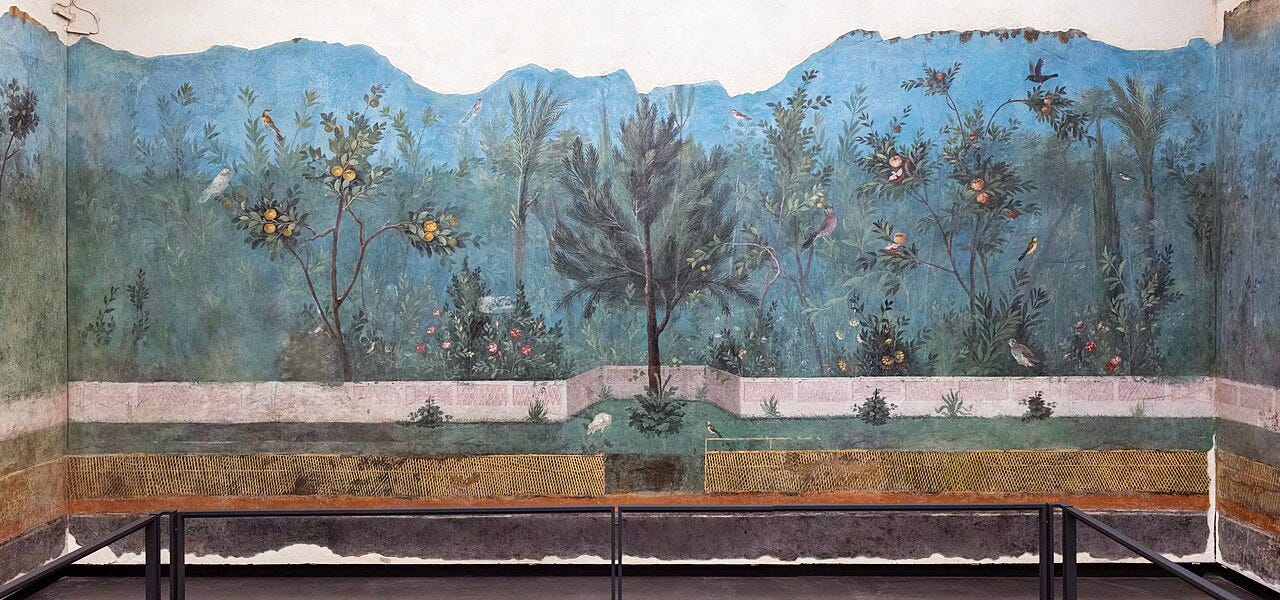

Since the first admission I met my psychiatrist once a week in his office. He wore dark rimmed eyeglasses, a dark suit and tie with crisp white shirt. His ergonomic black office chair behind a mahogany desk. Above and behind his head hung a reproduction of the painted garden from the Villa of Livia. The original was a large mural, created more than two thousand years ago.

As we talked, I stared at the painted garden. In the parallel world of my imagination I walked through its tall grass, listened to leaves rustle in a gentle breeze. The sky always faded baby blue. Plants flowered and fruited simultaneously, out of season. There, I was peaceful, relaxed, curious. It felt more bearable to speak about the difficulties of my real life because they did not exist in this idyllic paradise.

We discussed strategies for managing my symptoms. I noted their patterns, to better identify them in the moment, then reduced their severity using skills I'd learned from him or the hospital psychologists. I practised, including during scheduled weeks at home. He assigned tasks for me to complete.

Our conversations became more philosophical. He told me an Indian proverb.

'If your plans turn out as intended, good. If not, even better.'

He didn't say it was about God. But it reminded me of the biblical passage Jeremiah 29:11, "For I know the plans I have for you,' declares the Lord, 'plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you a hope and a future."

Either way, it helped me let go of the life I had imagined for myself – the one that smashed irreparably into a brick wall – and sparked hope that the unimagined life might be better anyway.

I began to understand that multiple experiences inflicted upon me from mid-adolescence to late-twenties were not normal. It was normal to develop mental illness in response.

Yet because these experiences happened as I entered adulthood – and recurred – I assumed that's how everyone behaved, outside the bubble of our family and childhood friends. I thought there was something innately wrong with me, faulty, because I could not go on as if everything were ok. I suspect this is how many severe mental illnesses begin.

The enforced socialisation in hospital with patients from a cross-section of society, including police and military, showed me that most people are decent. Though we all have flaws, we misunderstand, make mistakes, are at times selfish or careless. Sometimes we are dysfunctional.

And then there are those who repeatedly plot against, harm and exploit others, facilitated by people who look away. It is deeply painful to face this reality – and necessary, to protect ourselves and the more vulnerable.

Psychologist and internationally recognised expert on sexual predators, Dr. Anna Salter, advised that "We must know something about malevolence, about how to recognize it, and about how not to make excuses for it. We must know that we cannot expect fair play."

While researching how to recognise signs of malevolence, to evade being re-victimised, I was struck by the clear patterns of evil behaviour. Given the profound damage caused by malevolent acts I expected something more sophisticated. The areas of complex skill were in manipulation and lying to escape consequences, yet they were still unoriginal and repetitive.

As renowned novelist Toni Morrison said, 'Good is just more interesting, more complex, more demanding. Evil is silly. It may be horrible but at the same time it's not a compelling idea. It's predictable, it needs a tuxedo, it needs a headline, it needs blood, it needs fingernails, it needs all that costume in order to get anybody's attention. But the opposite – which is survival, blossoming, endurance – those things are just more compelling intellectually, if not spiritually, and they certainly are spiritually.'

At night, surrounded by the wreckage of malevolence – from which I had yet to see anyone heal – I considered the possibility that I had not been forsaken after all but saved from a worse fate.

Over the years hospital routines became familiar, comforting. I knew all the staff by name. I liked them. Other long-term patients become close friends. We were safe and protected.

During scheduled stays at my mother's house, I was on edge. My social skills had deteriorated. The cacophony of everyday sights, sounds and smells was overwhelming. I counted down the days to readmission – and relief.

I showed my psychiatrist a copy of Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama and explained that she had lived in a psychiatric hospital since 1997, working each day at a studio nearby.

'She's considered one of the most successful female artists of all time.'

Silent, his lips pressed into a thin line.

On a sunny day, when I could paint again, I told my psychiatrist, 'There is one more thing.'

He raised his hand, palm facing me.

Stop.

'No. You've been here too long. You are becoming institutionalised. If you stay, you will regress. You are making good decisions. You are capable. Whatever it is, you must go back into the world, rebuild your life as an artist, and deal with it there.'

He had a point. Thirty-something hospital admissions over five years. Weeks and months at a time, more than two years solid. The lifespan of three thousand lilies.

I wondered if he realised that what I intended to tell him was worse than everything else and happened within the artworld. Maybe that's why he said I should return. Perhaps it could not be resolved at a distance, from within the cocoon of hospital.

A rush of fear. Previously athletic, I was easily fatigued, with constant burning pain in weakened muscles. Though my movement had improved, dystonic seizures came and went in unpredictable waves. I could paint – just – but my handwriting still looked like I'd had a stroke. There was no clear path. I didn't know who I could trust, there.

My gaze shifted from psychiatrist to the painted garden behind him and lingered on the blossoming flowers, bright growth of foliage and trees laden with fruit. I thought about how much I had recovered under his guidance. And of the nurses' explanation that no-one leaves psychiatric hospital completely well, the final stages of healing happen outside it. I felt little hope but saw only two options: dare to try or wither in the same place I'd been revived.

'Okay.'

I stifled tears. My psychiatrist's face glowed with a soft smile. He nodded. I remembered my father's beaming expression when he was proud of me for accomplishing something difficult.

'Good. You leave tomorrow. You will always be welcomed here. But you must not come back.